The train stopped. Through the gaps between the sliding doors, Abram could see a series of low buildings and a beehive of activity. People in military and NKVD uniforms screamed at everything and everyone. Columns of raggedly dressed people marched towards the horizon. A truck rumbled by carrying giant logs. Another truck followed, pale sunlight glinting off rolls of barbed wire the truck bed. The train sat amid all this chaos, unmoving.

Abram drifted off to sleep.

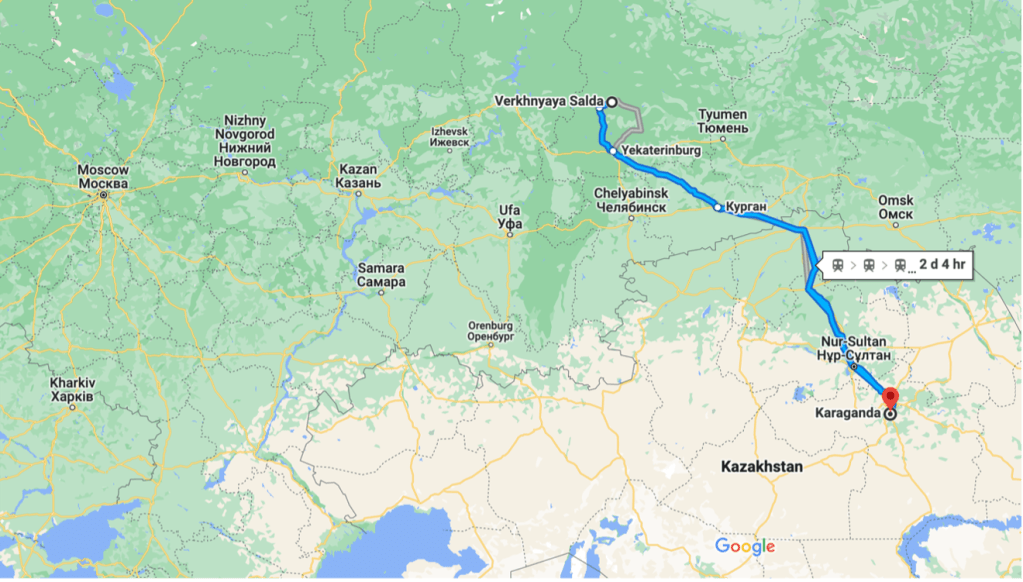

The doors of the cattle car rolled open with a loud clang and a flood of light filled the train car. Abram lost his balance and started falling out of the open doorway when a couple of arms grabbed the front of his shirt and pulled him back in. A group of NKVD soldiers screamed at the prisoners to get off the train and to line up along the rails. Very few could get out of the train car on their own – weeks of sitting in cramped spaces with barely any movement and very little food and water made everyone extremely weak. Abram did not keep track of the time, but one of the prisoners later told him that the trip from Verkhnyaya Salda to Karaganda took 17 days.

As prisoners tried to help each other get down from the cattle car, the guards were getting more impatient and angrier by the second. After a few minutes, the guards escalated from screaming to prodding prisoners with the butts of their rifles; a few minutes later kicks and punches rained down on those who could not line up quickly enough.

An NKVD officer in an immaculately pressed uniform and shiny cavalry boots paced in front of a ragged line or half-starved prisoners, his hand on the cover of his gun holster. He looked like he would have been happy to shoot them right there and then if his orders did not demand otherwise. Finally, he stopped pacing and faced the line.

“Listen up! If it were up to me, I would shoot you like the ungrateful traitor dogs that you are. However, our beloved father Stalin decided to forgive your betrayal of our motherland. He is giving you a chance to redeem yourselves. Through hard work you will help our motherland to defeat the Nazi invaders! Through hard work you will help our motherland to spread the power of communism to the working classes of the entire world! Through hard work you will make the Soviet Union the most industrialized nation in the world! Through hard work you will have a chance to redeem yourselves!” And then he said the words to which Abram would wake up every day for the next eleven years, words that would become the nightmare of his life – “Daesh Strane Uglia![1]”

“Daesh Strane Uglia!” – “Give Your Country Coal!” became the omnipresent motto of the last war years and of the decades following the war. The country was in shambles, and it needed the energy resources to rebuild. It needed resources to rapidly industrialize. It needed coal. “Give Your Country Coal!” became a cry that killed millions of people spared by the war. Very conservative historians estimate that almost six million people died in labor camps mining coal. Countless thousands died during harsh Russian winters, frozen to death in their unheated apartments because the precious coal could not be spared for such needless commodities such as heat. Abram saw that motto on a blood-red banner stretched right outside of his barrack, above rows of barbed wire. “Give Your Country Coal!” was the first thing he saw when he woke up and the last thing he saw when he went to bed. “Daesh Strane Uglia!” – “Give Your Country Coal!”

Karanada ITL, or Karlag. ITL stands for “Ispravitelno-Trudovoi Lager”, or “corrective labor camp”.

Karaganda ITL was one of the largest labor camps in the GULAG system. It was originally created in the early 1930s and covered a vast territory in Central Kazakhstan almost the size of France. The chain of prison camps, mines, factories and farms that made up Karaganda ITL spanned from Akmolinsk in the north of Kazakhstan to river Chu in the south.

The Soviet Union was rapidly expanding and colonizing the “national fringes” of the country and needed cheap labor to work the land and to mine the natural resources. For the cost of a bowl of balanda and a couple of slices of black bread millions of prisoners were building the national wealth of the country.

They did not call Karlag a “labor camp”. Instead, all official documentation referred to it as “NKVD Sovkhoz[2]”, an industrial-scale collective farm owned and operated by the Soviet government. By the mid 1930s, Karlag was probably the largest forced labor “sovkhoz” in the country, spanning 260 km north to south, and 100 km from east to west.

KarLag was not created on an empty spot in the middle of the steppe. When Soviet geologist discovered coal in steppes around Karaganda, the entire region was populated by indigenous Kazakhs, as well as Russians, Ukrainians and Germans who moved into Central Kazakhstan during the 1900s. In 1931, as the camps were being created, thousands of local people were forcibly removed from the area, often by the NKVD troops.

The lives of the indigenous Kazakhs turned out especially tragically. During the 1930 the Soviet government was collectivization in Kazakhstan. Local people, who for hundreds of years have lived lives of nomadic herdsmen, were moved to nearby towns where they worked backbreaking 12-hour shifts in factories, building the military and industrial power of the homeland.

Untold amounts of cattle were confiscated and people who did not want to work in factories or join collective farms were literally left to starve. Those who tried to resist were either shot or ended up on the other side of the barbed wire.

After the local population was removed or exterminated, hundreds of thousands of prisoners marched through the abandoned steppe, building barracks, houses, and railroads.

The ITL was kind of like the Vatican, a country within a country. The camp had its own system of government that reported only to NKVD in Moscow, its own courts, prisons and even a post office for communicating between different areas of the camp.

It was impossible to run away – no matter where you ran, you still ended up in KarLag.

The Karaganda basin was so incredibly rich with coal that there was no need for drilling mineshafts and going underground. Most of the time the coal was extracted using pit mining – a method that required virtually no machinery.

The area around the camp looked like a giant anthill. Thousands of Zeks went back in forth, digging, shoveling coal, loading wheelbarrows and carting coal. Why would the Soviet Union spend precious currency on expensive machinery when there was an endless supply of slave labor?

By the time of Abram’s arrival, Karlag was like a giant sprawling metropolis, with its own law enforcement, court, and even a jail. Talk about irony, a jail within a forced labor camp. The infrastructure even included a leather goods factory, a dairy plant, a meatpacking facility, a mill, metalworks, and educational facilities for the volnonayomnye[3].

As a trained machinist, Abram’s time was too valuable to waste in a cell awaiting execution. After being assigned a spot in a barrack, he and four other prisoners were escorted to a machine shop and put to work machining replacement parts for mining equipment.

That first night at Karlag, Abram learned about prison hierarchy.

Many years later, in 1993, after the fall of the Soviet Union, Abram’s grandson would bring a small book from school. Abram has never heard of the author, but one phrase in the book shocked him. “The positions of trust were given only to the common criminals, especially the gangsters and the murderers, who formed a sort of aristocracy. All the dirty jobs were done by the political[4].”

Most barracks had a bugor[5] – a man who one way or another commanded the respect and fear of other prisoners. All bugors reported to the korol’[6] – a man who regardless of his official “prisoner” status literally ran the prison, including the guards and some of the NKVD officers.

The absolute worst thing that could happen to anyone was to become a petuh[7]. Essentially, some weaker men were sodomized and became bitches to the ones who were stronger. The most common way to become a petuh was to lose at cards and end up unable to pay off your debt. Petuhi weren’t allowed to talk to other prisoners unless they were addressed first, they weren’t allowed to eat or drink at the common table, and they were forced to sleep next to the parasha[8].

Nights in Kazakhstan’s steppes get incredibly cold, with night temperatures falling to just a few degrees Celsius even in the summer. Abram was still suffering from headaches and shied away from bright lights and loud noises. When he returned to the barrack in the evening, he made his way to an empty nary in a dark, seemingly quiet corner, away from the door and the windows. As soon as Abram sat down and closed his eyes, someone grabbed the collar of his vatnik and threw him on the floor. Abram opened his eyes and saw a large bold-headed man in an unbuttoned vatnik over a stained wifebeater shirt. Faded tattoos decorated the man’s chest, neck, and knuckles. He leaned down over Abram and grinned, showing metal front teeth. “This is not your khata!” – said the man. “You walked into someone else’s house and laid on someone else’s bed, all without paying respects or asking permission.” Confused, Abram said something in Polish. The man turned to someone behind him and laughed. “Look, another inostranetz – zasranetz[9].” The man turned back to Abram and dragged him upright. “Do you speak Russian, inostranetz – zasranetz?”

Abram nodded. “In that case,” – the man grabbed Abram’s collar again and dragged him over to the nary near the wood stove, “introduce yourself to Mikhail Ivanovich.”

Mikhail Ivanovich was a short stocky man in wire-rimmed glasses. He perpetually wore a soft military cap, the kind that officers in the White Army used to wear during the civil war. Faded tattoos of cathedral domes peeked from his unbuttoned shirt. He spoke in a very soft tone, almost a whisper, but when he would say something, the entire barrack would go quiet, people would stop everything and listen.

Mikhail was apparently a man of few words. He nodded to the giant man who was still holding Abram’s collar and said, “Ob’yasni inostrantzu[10].”

Abram slowly settled into the rhythm of the camp life. Even though he was a political prisoner sentenced to death, he was a valuable commodity. Most prisoners around him were kulaks, formerly wealthy peasants who refused to cooperate with Soviet collectivization and refused to give up their cattle, grain, and farming equipment. The second largest group consisted of intellectuals, many of them from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. These people did not do anything wrong, except for being born in the wrong country at the wrong time and speaking the wrong language. Abram was one of the few prisoners who had experience with the machinery, understood and loved the simple mechanics of milling machines, lathes, and drill presses. He could look at a broken part, imagine what it looked like new, and machine a perfect replacement.

The machine shop was set up in a long cement-block building that in its past life probably held livestock. The two opposing walls were lined with narrow stalls, some of the stall walls knocked down to make room for the workbenches and the machines. Many of the machines were ancient, belonging in a museum or in a scrap yard instead of a machine shop. Two of the woodturning lathes were operated by a foot pedal and judging by their general condition and construction were probably made sometime towards the end of the 19th century. The cement-block walls were topped with a corrugated iron roof. In the summer, the building would get incredibly hot. In the winter, the prisoners burned garbage and scrap wood in a large metal drum to keep their hands warm enough to work.

The prisoners worked 10-12 hours per day, seven days a week. Every day they were told that according to plan the miners had to bring up a certain amount of coal. Based on that estimate, the powers that be also estimated the approximate amount of damage to the tools and to the machinery and gave repair quotas to all Karlag machine shops. The food rations depended on the prisoners’ productivity. Officially, there were six levels of food rations. Ration levels one and two were for the prisoners held in solitary confinement and in SRB – Special Regime Barrack. Rations three and four were for the ground workers, and rations five and six for the miners. Here’s how the rations worked, at least on paper:

- Ration 1 – 300 grams of bread and hot water

- Ration 2 – 350 grams of bread and hot water

- Ration 3 – 750 grams of bread and soup

- Ration 4 – 850 grams of bread and soup

- Ration 5 – 950 grams of bread, soup and a little bit of pork

- Ration 6 – 1 kilogram 100 grams of bread, soup and meat

Even though the food quotas were officially set, the system didn’t always work. Very often Abram and his machine shop mates worked to the point of complete exhaustion, but still wouldn’t get the deserved portion. Sometimes food shortages were caused by supply chain breakdowns. Sometimes food shortages were caused by guards selling prisoners’ rations on the black market. There was no one to complain to.

Almost seven months have passed. Barrack machine shop barrack. Barrack machine shop barrack. At some point, Abram almost forgot that he was sentenced to death – it was almost as if the NKVD and the camp administration forgot to execute him. In the evenings, in hushed tones, he talked to other condemned political, hoping that as long as they prove to be valuable workers the system would find it profitable to keep them alive. And then, who knows – maybe Stalin will die, and the system will change. Abram became close friends with a man by the name of Samuil Gotgilf, a doctor from St. Peterburg. In his previous, pre-Karlag life, Samuil was a general surgeon, a well-respected doctor who graduated top of his class from a Kuybyshev Medical institute. He was obsessed with genealogy could trace his family tree all the way to the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492, through centuries of Jewish settlements in Prussia, Saxony, Bavaria, Poland, and eventually, Russia. He spoke Yiddish, German, Polish, French, and Russian and sometimes would launch into long whispered monologues about rare diseases.

In Karlag, no one cared about Samuil’s medical achievements. For the most part prisoners weren’t valuable enough to warrant a doctor. If they got sick and died, there were plenty more where they came from. Instead of treating humans, Samuil was assigned to report to the camp’s veterinary, an old Kazakh man with a wispy beard and unnaturally smooth skin, stretched tight on his perpetually smiling face. Thanks to Dr. Gotgilf’s job, the prisoners in his barrack occasionally had extra food, food that was originally earmarked for the animals. However, beggars cannot be choosers – mushy carrots or last-year’s apples made a nice addition to the daily balanda. By sneaking animal feed Dr. Gotgilf saved hundreds of prisoners from scurvy. No matter how exhausted he was, he would always help the men in his barrack, treating anything from boils to broken fingers. A few years later, he would save Abram’s life.

Once a month, in addition to their normal rations, prisoners would get about half-a-kilo of molasses, a brown gooey sweet substance left over from refining sugar beets into sugar. In 1942, that sweet sticky goo was a luxury granted to inmates by the camp administration of one of the worst camps in the GULAG system. To the prisoners, it was the nectar of gods that allowed them to sustain our lives for a bit longer.

Long before the war, Abram had once read that there are some African tribes who believe that if a warrior ate a fallen enemy, he would gain his strength and courage. Something similar was practiced in many of the camps, although somewhat metaphorically. While inmates did not actually eat each other, they might as well have. Ugolovniky took hey just took food from others who were weak and lacked protection. They took food, the only thing that kept many prisoners semi-alive in those inhumane conditions – a GULAG version of African cannibalism. The monthly portion of molasses was better than any currency – one could trade it for bread, soup, tobacco, or give it to the ugolovniky to win favors, or to the hospital workers to arrange for sick days.

There was a narrow four-step staircase that led to a tiny, barred window that separated the person handing out molasses rations from the rest of the prisoners.

That day Abram got lucky; he was one of the first to the window and an unseen hand dumped half-a-kilo of the brown mass into his tin. Once a prisoner got his molasses, he immediately became extremely vulnerable. He had to hold the tin with both hands – spilling molasses wasn’t an option. At the same time, he had to get down the rickety staircase and wade through a mass of screaming pushing people. The only way to get out was to climb over the railing, jump off the top of the staircase and pray that you land on your feet. If you fell, at best someone would just rip the tin of molasses out of your hands. At worst, you would die – there were always people hiding under the stairs, ready to stab anyone for an extra portion of molasses.

Abram held the precious tin close to his chest and heaved his body over the railing. Unfortunately, the landing wasn’t as good as he hoped for – Abram’s feet slid in the mud, and he ended up flat on his back. Before his body even hit the ground about a dozen people appeared from under the staircase and reached for his tin of molasses. He fought as hard as he could – kicking and biting. At one point, Abram managed to get up and for a moment thought that he might actually escape. He headbutted the man who was standing between him and path back to the barrack and tried to sprint away from the mele. He almost made it. Someone jumped on Abram’s back, bringing him to the ground and spilling the precious molasses. The last thing Abram remembered was something sharp sliding under his shoulder blade. Twice.

Abram opened his eyes to a whitewashed ceiling. He tried to look around, but a tight bandage pressed against his forehead held his head firmly against the mattress. He tried to touch his face, but his left arm was bound to the side of his body. “You are awake!” – said a familiar voice. Samuil Gotgilf leaned over Abram and lightly touched his shoulder. “You must have at least nine lives, “– said Samuil. “You’ve been stabbed twice, and the second stab wound barely missed your lung. You’ve been unconscious for four days. You are still not quite in the clear – so far, your wounds look clean, but there are no antibiotics. I cleaned them the best I could with what I had, and I stitched you up, but your wounds might still get infected. We’ll just have to watch and see.”

Samuil untied the bandages that held Abram’s head against the mattress and helped him to sit up. Abram’s throat felt on fire – he did not remember ever being this thirsty. “You probably want this,” – Samuil handed Abram a large tin of water. “Drink slowly.” Abram nodded and wet his lips.

“You don’t even know how lucky you really are,” – said Dr. Gotgilf. “You still remember that you were under a death sentence?”

Abram set the water tin down and nodded.

“Well, apparently the orders came from above to carry out all death sentences. Two days ago, they took about 30 people, loaded them in trucks, and told them that they were moving them to a different sector. Later we found everyone who was ‘moved’ was executed. I saw the lists – you were supposed to be on those trucks.”

Abram drew a deep breath. “Do you know if they will still execute me? Or did I fall through the cracks in the system?”

Dr. Gotgilf stood up and walked to the door. He looked outside, closed the door, and walked around the small room, checking the windows. After making sure that there was no one to hear them, he leaned over Abram and whispered. “I don’t know for sure, but a few days some NKVD colonel from Moscow arrived with a bunch of papers. They were all drinking, and the next morning he woke up with chest pains. He hospital doctor was apparently drinking with them and was too hungover to even understand what was going on. Someone actually remembered that I’m a real doctor and I was called for a consult. They left me alone in the colonel’s office for a few minutes, and I saw some lists and letters on his desk. I am not completely sure, but I think that they identified specialists who are good mechanics, doctors, engineers, or those who are trained in operating heavy machinery. Everyone who made that list will be shipped to other camps. I am not sure what would happen to the ones who were sentenced to death, but I think most likely your sentences will be replaced with at least a decade of hard labor. “

Abram spent almost three weeks in the infirmary. For the first couple of week or so, Dr. Gotgilf would visit him every night. Then the visits suddenly stopped and Dr. Gotgilf simply disappeared. Abram guessed that he was one of the “valuable” prisoners that were shipped to other great labor camps.

When Abram returned to his barrack, he asked Mikhail Ivanovich, the barrack’s criminal boss, if he knew anything about Dr. Gotgilf. Later that night, a man came up to Abram’s nary and handed him a piece of paper. “From Mikhail Ivanovich,” – the man said and walked away. Abram turned to the wall and unfolded the paper. Dr. Samuil Gotgilf was sentenced to 10 years of hard labor and transferred to Vorkuta.

A few days later, during the morning roll call, an NKVD officer whom Abram had not seen before handed the guard a sheet of paper. The guard saluted and quickly scanned the page. He looked up at the prisoners and started calling names. Guards quickly pulled those whose names were called to the side. When Abram’s name was called, he immediately moved into the new group, before the guards even had a chance to reach for him. After calling about 20 names, the guard saluted the officer again and handed back the sheet of paper.

Guards marched the selected prisoners to a dusty patch of ground next to the gates. Prisoners were ordered to sit on the ground and wait. Abram did not know what to think – was Dr. Gotgilf right and he was simply one of the specialists being transferred to another camp? Or was he about to be executed? The thoughts should have been terrifying, but Abram felt strangely calm. He just survived two stab wounds. Maybe Dr. Gotgilf was right when he said that someone was watching over Abram?

Abram rolled a cigarette and waited. They sat for what must have been two or three hours before a military transport truck rolled through the gates. A young officer jumped down from the passenger seat. He pulled a several sheets of paper from a shiny brown leather satchel and handed them to one of the guards. The guard saluted and ran off to get his superior officer. About 10 minutes later an older NKVD captain appeared and handed the papers back to the young officer. They exchanged a few words and the young officer said something to the guards. Immediately, the guards started screaming at us and waiving their riffles. “Davai, skoree! Move it! Get up!” Even though everyone was moving of their own accord, the guards prodded and pushed the prisoners until everyone was in the truck. Two of the guards jumped into the truck bed with the prisoners, and another guard rolled down the canvas flap.

Abram and hundreds of other prisoners from Karlag were sent “po etapu”. The word “etap[11]” comes from the French “l’étape”, meaning a place of rest along the way of a long trip. “Po etapu” was a traditional method of transporting prisoners in Tsarist Russia from urban centers such as Moscow or Sankt Peterburg to exile in remote locales of Ural or Siberia. Along the way, there were villages, or special facilities, where prisoners and guards could temporarily stay and rest. The NKVD adopted the same idea for transporting prisoners to various camps, as well as transferring prisoners between different camps of the Gulag system. More often than not, etapy were simply train stations, where prisoners sat locked in train cars and waited to be attached to a train going in the right direction. Sometimes, when no trains were available, prisoners had to move on foot.

Vorkuta is almost directly north of Karaganda, a little over 2000 kilometers as the crow flies. The etap from Karaganda to Vorkuta usually started at the Karaganda train station, but for some unknown reason no trains were available. When the guards finally allowed the prisoners to get out of the truck to relieve themselves, Abram counted somewhere between 15 and 20 trucks sitting near a stretch of train tracks. The prisoners were given water and bread; every hour or so the guards would take turns and sneak out of the truck for smoke breaks. Abram did not have a watch, but at least 24 hours had passed from their arrival to the train station. He could hear more trucks arrive, guards arguing outside, someone shouting orders. Every few hours the prisoners would be allowed to relieve themselves; once more, in the morning of the next day, they were given more water and bread.

By the midafternoon of the next day, without any warning, the trucks started moving. “Where are we going?” asked one of the prisoners. Someone tried to shush him – asking questions almost never produced useful answers, and more often than not resulted in a beating or some humiliating activity. To everyone’s surprise, the guard turned to the prisoners and told them that they were ordered to transport everyone to Akmolinsk, a town about 200 kilometers from Karaganda.

During World War II, as the German army advanced across the Soviet Union, the government ordered a massive evacuation of factories from Ukraine, Belorussia, and Russia. Entire factories were disassembled and moved to various areas of Kazakhstan. Akmolinsk served as a transport hub of engineering tools and equipment from evacuated plants. Many of the evacuated plants were reassembled and retooled to serve war needs, and Abram hoped that his expertise with machines would get him pulled from the Vorkuta etap and keep him in Kazakhstan.

The 200-kilometer drive from Karaganda to Akmolisk took almost two days. Several times one or more trucks broke down and the entire convoy would stop and wait for the repairs. A couple of times the convoy would pull to the side of the road and wait for ours to allow other trucks loaded with heavy machinery to pass. Once a day, the prisoners would get water, but no food. One time, on the morning of the second day, the guards pulled Abram and a few other prisoners from their trucks and ordered them to fix an axle on a transport carrying mining equipment from Ukraine. The guards did not want to unload the heavy equipment and ordered the prisoners to fix the axle on a fully loaded truck. The repair took almost four hours, and in the end, other prisoners were pulled from their respective trucks to unload and then reload the mining equipment. Once the repair was complete, one of the drivers from the equipment transport gave Abram and his group of prisoners half a loaf of bread. The bread was gone before they made it back to their trucks. The prisoners were unloaded from the trucks near Akmolinsk towards the end of the second day. The guards received orders to wait for a special train that would stop on the outskirts of the town; once the train would arrive, the prisoners would be loaded into retrofitted cattle or cargo cars and head north, to Vorkuta.

[1] Даешь Стране Угля!

[2] Sovkhoz – an abbreviation of of Russian Sovetskoe Khozyaystvo (lit. “soviet farm”)

[3] Volnonayomnye – lit. “free workers”. Employees who worked in prison camps / labor camps but were not prisoners themselves.

[4] George Orwell. 1984

[5] Bugor. Russian “бугор” (lit. “hill”)

[6] Korol’. Russian “король” (lit. “king”)

[7] Petuh. Russian “петух” (lit. “rooster” or “cock”)

[8] Parasha. Russian “параша”, prison toilet.

[9] Russian: иностранец-засранец (inostranez – zasranetz) – foreigner – asshole

[10] Russian: объясни иностранцу(ob’yasni inostrantzu) – explain to the foreigner

[11] Russian “этап”

You must be logged in to post a comment.