My grandfather almost never talked about his past. Whenever I would ask him about his childhood, my grandfather would tell me a few disjointed stories that did not really shed any light on who he was or where he came from. One story that he told me again and again was about a few of his friends betting that he would be two afraid to poke a bull with a stick. After my grandfather proved them wrong, the bull chased after my grandfather, eventually tossing him a few meters across the field. In another story, he joined the Maccabees, a Jewish youth athletic team. Supposedly he was so flexible and strong that he quickly earned the nickname “Acrobat”. That was it. Not details, no background. Just the bull and the Maccabees.

I wasn’t completely oblivious and did notice little odd things about his behavior. Living in the Soviet Union, it was customary for everyone to pay lip service to the Communist Party, to praise the General Secretary and the party policies. In our house, politics was a taboo. Whenever a guest would try to start a slightly controversial conversation, my grandfather would always change the subject.

When I was five years old, my preschool class put on a show for the October Revolution Day. I was supposed to take the stage in front of all the kids, their parents, and observers from GorKom (the city committee), and recite Samuil Marshak’s poem “The Day of 7th of November.”

| День седьмого ноября – красный день календаря. Посмотри в своё окно всё на улице красно. Вьются флаги у ворот, пламенем пылая. Видишь, музыка идёт там, где шли трамваи. Вся страна – и млад, и стар – празднует свободу, и летит мой красный шар прямо к небосводу. | The day of 7th of November is a red calendar day Look out your window everything outside is red Flags are waving by the gates like red flames Look, they are playing music where trams used to run The entire country – young and old are celebrating freedom and my red balloon is ascending towards the sky |

I proudly read the poem and everyone in the audience applauded. When my teacher tried leading me off the stage, I decided to improvise. I started to tell a story about how Grandfather Lenin loved children so much that he told Grandfather Stalin and Grandfather Brezhnev to take care of the country’s youth, to make sure that children get good education and become good communists. I might have gotten my historic chronology somewhat wrong, but the bigwigs from GorKom were so charmed by my story that they gave my teacher a commendation for raising such wonderful, politically astute children. My teacher was so ecstatic that she came to our house and praised my parents and grandparents on raising such a wonderful boy. After she left, everyone congratulated me. Everyone except for my grandfather – he walked away from the celebration and planted himself in front of the TV.

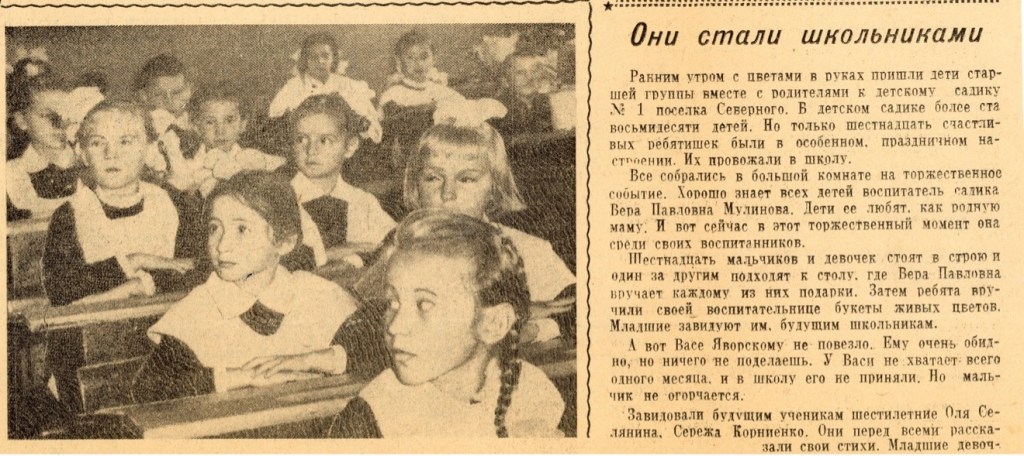

Occasionally I would hear stories about my mom’s childhood in Vorkuta. She reminisced about jumping off the roof into snow drifts and even showed me an old yellowed Zapolyarye newspaper. The newspaper featured an article about young school students, with a photograph of my mother’s first-grade class.

Once, I overheard a conversation between my grandfather and a few of his friends – they talked about being transported to Vorkuta and having to build railways as the progressed. When they saw me listening, they immediately changed the topic of their conversation.

My grandmother had three sisters – Maria, Bertha, and Beba. Maria, the oldest sister, passed away before I was born. Beba died from breast cancer when I was about five. While I don’t really remember her, I distinctly remember my grandmother’s devastation, an overnight train ride from Gomel to Kiiv, and the wake following the funeral. Bertha also lived in Kiev. She was a widow who did not seem to like anyone except for me. She frequently visited us, staying for weeks at a time. Every summer, my mom and I would stay with her and explore Kiev. Even though I have been lucky enough to travel all over the world, to this day Kiev is by far one of my favorite cities.

Whenever Bertha would visit, my grandfather would grunt a “hello” and not talk to her for the rest of the visit. He would go to any lengths to avoid talking to her, or even being in the same room. Years later, my mom finally told me about what happened between my grandfather and Bertha.

The USSR government went to extreme lengths to prevent its citizens from listening to uncensored radio broadcasts from western radio programs. Beginning in the late 1940s, the USSR started to use radio jamming to block political broadcasts of the British Broadcasting Corporation and the Voice of America.

In 1947, the Voice of America began broadcasting Russian-language programs into the Soviet Union, offering summaries of current events, and even offering glimpses of Western music.

My grandfather had an old VEF-TRANSISTOR 10 transistor radio. Someone had modified it so that it could receive short-wave transmissions. This transistor radio was my grandfather’s prized possession. He kept it near his bed, and no one was allowed to touch it. Every evening, my grandfather would close the door to his bedroom and tune in to the scratchy sounds of the Voice of America. “Слушайте, слушайте. Говорит Нью Йорк.” (Listen, listen. This is New York broadcasting.). My grandfather would stay glued to the radio for hours, absorbing every event and every rumor that took place outside of the iron curtain. He never discussed what he heard with anyone, not even with my grandmother. The only time he recounted what he heard on Voice of America ended up irreparably destroying his relationship with Bertha.

According to my mom, my grandfather was driving to Kiiv, with my mom, my grandmother, Bertha, and Bertha’s husband. At some point the conversation turned to the Prague Spring and the Soviet response to “communism with a human face”. My grandfather recounted an analysis of the events that he heard from the Voice of America. Bertha, who wasn’t a communist and did not belong to any political organizations. Surprised everyone by saying: “So, you listen to Voice of America? Maybe you deserved the time you spent in Gulag? Maybe I should call you-know-who and let them know that you are listening to illegal broadcasts?” By the way, Soviet people would always say you-know-who in reference to the KGB, and as I’m writing this, I keep thinking about the Harry Potter universe and the wizard community referring to Lord Voldemort as he-who-must-not-be-named.

After that threat, my grandfather cut Bertha out of his life. Shortly before his death, my mom asked him if maybe it is time to let it go. He took her aside, closed the door, and started crying. From what my mom told me, this was the only time in her life when my grandfather cried in front of another person. “You do not understand what kind of person she is. She was my family and she threatened to report me for listening to Voice of America. Me, who already spent ten years in prison for saying the wrong words at the wrong time in front of the wrong person!”

You must be logged in to post a comment.