My grandfather passed away on May 18 of 1999, at DePaul Hospital in Norfolk, Virginia. This was his seventh trip to the ER in the last month. Chemotherapy wiped out his platelets and the smallest jostles set off nosebleeds. Nosebleeds that lasted for hours. Nosebleeds that we could not stop. My grandmother would call me in terror, sometimes in the middle of the night. I would call 911, an ambulance would pick them up at their home and I would meet them at the ER. If I were stuck at work, or were outside of a cell service area, my grandmother would call my nine-year-old sister Olga – my mom would drive her to the hospital to translate for my grandparents.

Every time my grandfather ended up in the ER, we all thought that it would be the last. On that seventh time, on May 18th, the doctors told us that this was it. They stopped the nosebleed, but they told us that the only thing that they could do was provide palliative car.

My grandmother, my mom, and I took turns at his bedside. My grandfather kept slipping in and out of consciousness, calling people whose names I did not know, raving about prison camps, about shesterki[1] and about NKVD[2]. I pulled out my notebook and started jotting down his morphine- and pain-induced rants.

When my grandfather slipped into a coma, I put away my notebook. I went home for a few hours to get some sleep. About an hour after I fell asleep on the couch, my mom called and told me that he passed away.

I had to take care of the funeral arrangements and everything else that comes with having a loved one pass away. I had to pick up my little sister from the school bus and tell her that our grandfather just died. All and all, it was a pretty bad day. All the questions that I wrote in my notebook sat forgotten in my backpack.

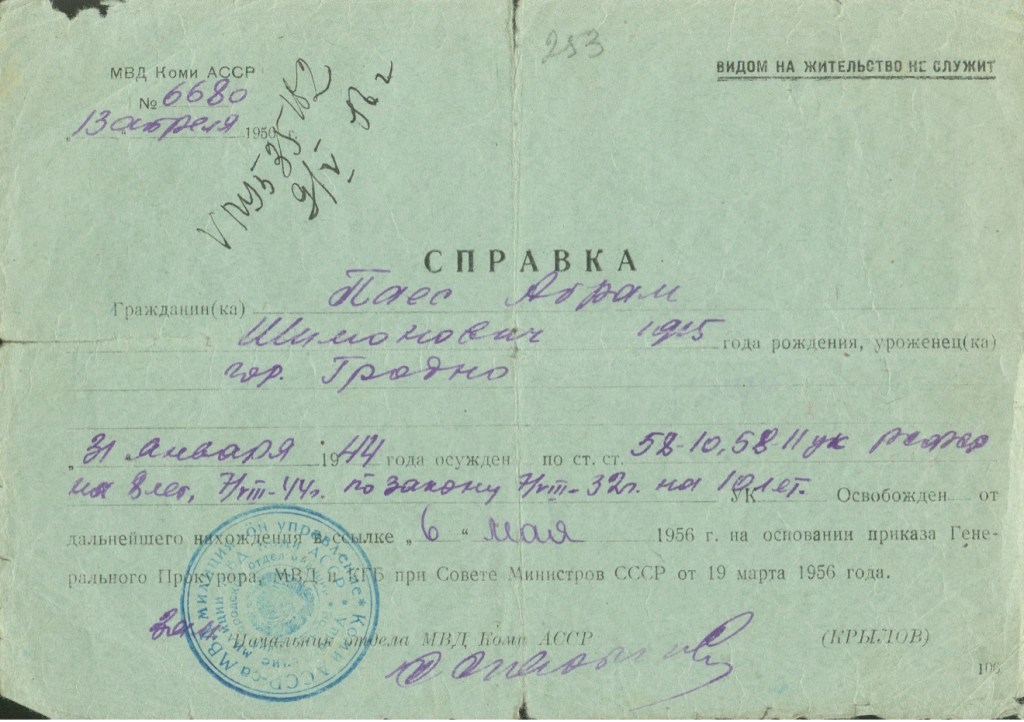

Months later, when work, school, and more work had dulled the pain a bit I leafed through my notes. I realized that even though my grandparents raised me, and even though I lived with them until I was 16, I knew next to nothing of who my grandfather was or what his life was like before I was born. I went through stacks of documents that were left after my grandfather’s death, but that raised even more questions. One document, a wrinkled blue piece of paper held together with bits of old surgical tape said in faded black ink that “Abram Shimonovich Payes was released from Vorkuta correctional facility in 1953 after serving a full 10-year sentence for violating article 58 subsection 10 of the Soviet criminal code”. Another document dated May 6, 1956, stated that “Abram Shimonovich Payes is released from exile”. All and all, I found about twenty documents that referred to labor camp sentences, release, and exile.

I knew my grandfather as Arkadiy Semenovich Payes. Who was Abram Shimonovich? Who was Sima Russ, listed on an old marriage certificate? My grandmother’s name was Olga Marchevskaya, not Sima. Who were all these people? Why was my grandfather in forced labor camps? These questions swirled in my head as I filled page after page with notes, questions, and translations.

It took me almost 20 years to finish this work. I started writing this book in 2003. I found people who knew my grandfather in Vorkuta, in Kazakhstan, in and Gomel. I tracked down former GULAG inmates who spent close to a decade with my grandfather in Vorkua GULAG. I spent hundreds of dollars on long-distance phone calls. I recorded hours and hours of interviews with my grandmother and my mom.

I combed through thousands of scans and microfiche from Grodno Archives (both from the Belorussian National Archives and the United States Holocaust Museum archives), and publicly available GULAG archives. I contacted Argentina National Archives, and poured over passenger lists from 1930 through 1940, looking for people who traveled from Poland to Argentina. I visited the reading room at the David and Fela Shapell Family Collections, Conservation and Research Center in Bowie, Maryland Maryland and flew to Florida to interview a former GULAG inmate who knew my grandmother. I wrote multiple letters to Memorial, a Russian non-profit dedicated to preserving the memory of GULAG atrocities. I submitted requests for information to Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), Vorkuta archives, Karaganda Archives, and Kazakhstan State Security Service. Letters from Vorkuta and Karaganda confirmed my grandfather’s incarceration, the article of the Soviet Criminal Code under which he was sentenced, the crimes for which he was sentenced, his transfer from Karaganda to Vorkuta, his release papers, and finally, his official rehabilitation papers.

While I was able to trace most of my grandfather’s path through the GULAG system, no mattery how hard I tried, I could not find anything about him from before 1942. My mom and I began to speculate that maybe he wasn’t really Abram Payes. During the Great Patriotic War, especially in the beginning when the German army steamrolled over Russia, it was a common practice to offer criminals a chance to defend their Motherland, to wash off their sins with blood. It was also not that uncommon for criminals to take documents from dead soldiers and use someone else’s identity to erase their past. We thought through dozens of scenarios. Abram grew up in Grodno and knew the Payes family. Abram served with someone from Grodno who told him stories about the town. Abram was a criminal conscripted to serve in the army. Abram was…

Finally, in 2022, after hitting another dead end, I posted a cry for help on the Jewish Genealogy Portal, a Facebook group dedicated to, as the name suggests, Jewish genealogy research. Several people quickly responded, suggesting that I reach out to Yuri Dorn, an archivist and a professional genealogy researcher from the Jewish Heritage Research Group in Minsk, Belarus. Yuri, a soft-spoken man with a professorial voice and a calm demeanor told me that Grodno archives were fairly complete and that even with the limited information that I had there was a pretty high probability of finding something about my grandfather. Over the course of about three months, Yuri and his colleagues dug into Grodno archives, combing through voter registrations, rental agreements, and synagogue records. At one point, two months into the search, Yuri emailed me with bad news. His team found information on the people that my grandfather mentioned by name to my grandmother and my mom – Bluma, Shimon, Leya, Asya, and Lisa Payes. From my grandmother, I knew that Shimon and Bluma were my grandfather’s parents, and Leya, Asya, and Lisa were his sisters. The bad news was that there were no records of Abram Payes – nothing in the Grodno Synagogue archives, no tax or voter records. Nothing.

My mom and I started speculating on what the absence of records could mean, coming back to the theory that maybe there was never an Abram Payes, only an impostor. I frantically began searching in other areas and archives. I reached out to Dr. Gregor Thum at the University of Pittsburgh History department, hoping that he might give me some insight on working with prison archives in Poland. Dr. Thum introduced me to Dr. Padraic Kenney, a history professor at Indiana University who specializes in researching how groups of people and individuals without power (such as prisoners) manage, survive, and resist in hostile environments. I read Dr. Kenney’s wonderful opus “Dance in Chains: Political Imprisonment in the Modern World”, I wrote to prison archives in Warsaw and Bialostok, and I spent weeks pouring through every Polish archive I could find with the help of Google Translate.

Just as I was getting desperate, I got one more email from Mr. Dorn. Just one line of text. “We managed to find a record of Abram Payes’ marriage!”

From that point, tracking the right records became easier. Mr. Dorn’s team found my grandfather’s rental agreements, his first wife’s family information, marriage witnesses, and voting records. Now I knew for a fact that Abram Payes was a real person, and while there is a possibility that my grandfather could have taken Abram’s documents during the war, the more facts clicked together, the more remote that possibility became.

Twenty years, many false starts, a wonderful supportive wife, two children, and a PhD later I finally collected enough information and wrote enough pages for whatever this is to qualify as a story. A book.

Throughout the following pages, I try to be as factual as possible, keeping names, dates, and events as true and as close to how they actually occurred as I possibly can. However, archives and interviews can tell only so much. I do not have any first-hand accounts and stories from my grandfather, so I really have no way of knowing how he felt when something happened, or how the train that transported him to Kazakhstan or Vorkuta really looked like. That being said, I have interviewed enough people who went through similar experiences with arrest, interrogations, beatings, starvation, impossible labor, and inhumane treatment that I can attempt to superimpose others’ feelings onto my grandfather’s story. I have seen enough photographs and heard and read enough descriptions of how prisoners were transported, of how political prisoners were treated, how Vorkuta mines looked like to hope that my descriptions are close enough to what my grandfather saw and experienced.

My grandparents never threw out anything. They weren’t pack rats by any means. It’s just that in the Soviet Union everything was so scarce that a rusty screw could (and would) be reused many times in many different projects, an old t-shirt could be used as a cleaning rag, and old newspapers cut into squares and used when stores run out of toilet paper. This “save everything” mentality also applied to documents, notebooks, random notes, and photographs. When my mom and my grandparents immigrated in 1996, they brought everything they could with them – old bed linens, dishes, kitchenware, and toilet paper. At least one of the suitcases was full of photographs, journals, notes, and documents.

To this day, this suitcase sits in my mom’s closet. Without it, this book would have been virtually impossible.

I started thinking about writing this book around 2002 or 2003. In 2000, I moved from Norfolk, Virginia to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania because of a job. I tried to visit my mom, my sister, and my grandmother as often as I could, but life kept getting in the way. In 2001, after the dotcom bubble bust, many companies went out of business and millions of software engineers ended up without jobs. I was one of the lucky ones and always managed to find a job right before a company that I worked for went under, or before my position was outsourced.

In 2003, I decided to go back to school. I was pretty burned out working as a software developer and wanted to do something different. Ever since I was a kid, I wanted to be a journalist. However, by 2003, it was clear that jobs in journalism were few and far between. Many journalism programs stopped admitting students; some disappeared completely, others got absorbed into communication departments. Since I’ve always loved reading historical non-fiction and has always been fascinated by historical research, I decided to give majoring in history a shot. That’s when I met Dr. William Chase.

In 2003, Dr. Chase was the Chair of the History department at the University of Pittsburgh. When I scheduled a meeting with him to discuss my study interests, I was very intimidated and worried. In Soviet culture, students do not meet with department chairs or deans unless there is a major problem. There is a very clear hierarchy in relationships, and a friendly conversation between faculty and students is not something that commonly happens. Sufficed to say, I walked into Dr. Chase’s office with some trepidation.

I was greeted by a kind-faced bolding man with a greying beard and wire-rimmed glasses. Dressed in khaki slacks, a faded blue shirt, and a pair of slippers, Dr. Chase looked perfectly comfortable and at home in a tiny office full of books, papers, and Soviet-era propaganda posters. He immediately made me comfortable. Instead of asking me about my academic plans, or about courses that I had taken in the past, he excitedly talked about Soviet history, about the economic and societal changes in the post-Soviet world, and about his research interests. He asked me about MY opinion and MY perspective on certain historical and current events, and he actually listened to what I had to say. Somehow, the conversation turned towards my family history, and I told him that my grandfather spent 11 years in Gulag. When Dr. Chase started asking deeper questions, I realized that I knew next to nothing about my grandfather or about the history of forced labor in the Soviet Union. As we continued talking, he abruptly stopped, looked at me and said: “You have to write a book about this. Register for an independent study with me and I will help you get started on your research.”

As I kid, I thought that someday I’d write a book, but I always imagined writing a sci-fi novel, something about exploring distant worlds, traveling across space and time, and saving the galaxy in the process. Up until that moment, I had never considered that my grandfather’s story would be of interest to anyone except for my family.

Next time I went to visit my mom in Norfolk, I opened the magic suitcase and started digging through documents and photographs. Many of the photographs had short descriptions, lists of names and dates written on the back in my grandmother’s tiny handwriting. Some of the names and faces were familiar – Mikhail Fishman, Lazar Golub, Pavel and Galina Zhizhiny, Gehrman Abram, Raisa and Ilia Rosinko, Mikhail Zaytsev. These people visited us in Gomel many times, and frequently stayed in our apartment for weeks at a time. When I was a kid, my grandmother and I would visit the Rosinko family in Riga, Latvia. In my teens, we spent a month almost every summer in Korosten, in northern Ukraine, on Pavel’s and Galina’s farm. These people were somehow connected, but how? How can I find them, on the other side of the world, at least 15 years after I last saw them? Are they still alive? Would they remember me? Would they remember my grandparents?

My grandmother knew only so much about who these people were and how they were connected to my grandfather. She told me that they were all related through Vorkuta GULAG, and that everyone on my list of names was a political prisoner in Rechlag, the main Vorkuta Gulag camp, sometime in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Everyone except for Pavel Zhizhin, who was actually a prison guard. It turned out that my grandmother still kept in touch with Mikhail Fishman. I vaguely remembered a short, plump, balding man, very talkative and quick to smile. My grandmother gave me her address book that contained a wealth of names and addresses of friends, friends of friends, relatives, and virtually anyone my grandparents ever met. Carefully leafing through the brittle brownish pages, I could see the changes in my grandmother’s handwriting over the years. Tiny sure letters of early entries slowly morphed into shaky, uneven lines of more recent addresses.

To my surprise, I found a Ft. Lauderdale, Florida address for Mr. Fishman – it turned out that he immigrated to the United States in the 1990s and kept in touch with my grandparents over the years. I asked my grandmother to call Mr. Fishman and see if he would be willing to talk to me about his years in GULAG, what he knew about my grandfather’s life, and if it would be OK for me to call him, or even visit him in Ft. Lauderdale.

[1] Shesterka (Russian: шестерка, from the Russian word шесть, meaning six) – a Russian prison slang term for “snitch”.

[2] The NKVD (Russian: Народный Комиссариат Внутренних Дел [Narodniy Kommissariat Vnutrennih Del], English: People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) was the law enforcement organization in the Soviet Russia and later in the Soviet Union. NKVD was the precursor to the KGB.

You must be logged in to post a comment.