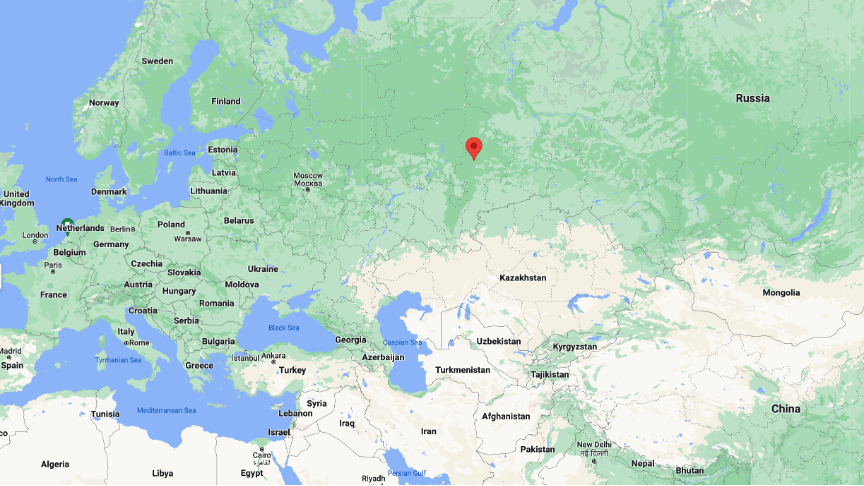

On April 19, 1943, Abram was transported to Verkhnyaya Salda, a small town near Sverdlovsk, in the Ural region.

Captain Streshnev warned Abram several times in no uncertain terms about what would happen to him if he were to go back on the confession.

The headaches were brutal – days of beating must have taken their toll, and Abram tried to keep his eyes closed and his head still as much as possible. The interminable ride in a horse-drawn telega, a transfer into a tarp-covered military truck, a jostling ride over unpaved country roads to Verkhnyaya Salda, no water or food. Every time Abram opened his eyes, his head exploded with pain.

The actual court session was a blur. Abram knew that it would not be a fair hearing. These court sessions, even during wartime, were just for show. He simply confirmed what Captain Streshnev wrote in his confession and signed a few more papers without reading them. Abram expected that just like everyone else whose case was heard before his, he would be sentenced to 10-15 years of hard labor and 5 years of exile. When the judge announced a death sentence, Abram thought that he heard wrong. He opened his eyes, a wave of pain and nausea flooding his head. When the guards tried to lead him away, Abram began to fight, struggling to get back into the courtroom. “I did not do anything wrong! Streshnev made it all up! He beat me until I signed the confession. Let me go! Let me go!” One of the guards let go of Abram’s arm and hit him on the side of the head with the butt of his rifle.

Another truck ride to the train station. There were about 40 of us, prisoners accused of being spies, saboteurs, wreckers, and traitors. Glazov and the university professor were already there – they each got 15 years. There was also a man by the name of Samuel Gotgilf, a medical doctor. A few years from now, he would play a major role in Abram’s life – he would save Abram from a hungry death.

The truck sat at the train station. The prisoners were packed so tightly in the truck bed that it was impossible to lay down. Many were afraid to ask if they could relieve themselves, and the smell of sweat, dried blood, and piss was overwhelming. More trucks pulled up, all just as packed with human bodies.

In the morning, soldiers walked around the platform and told the prisoners to check their trucks for anyone who had died during the night. Thankfully, no one died in Abram’s group, but he could see bodies tossed on the ground from at least four other trucks.

By the late afternoon, a long train snaked its way into the station. A combination of cattle cars mixed with open platforms and coal carriers was pulled by an old steam locomotive. Two passenger cars bracketed the train on either side.

The soldiers began calling names from a long list, pulling prisoners off trucks, and shoving them into cattle cars.

As the men were loaded into the train, one of the prisoners slipped on an oil puddle and fell. As he struggled to get up, one of the guards stepped on his shoulders pinning him to the ground and said, “This is where the Soviet democracy ends for you. From now on, polar bears will be your judges and wolves will be your friends.”

Abram kept his eyes closed through most of the process.

The train car was packed. In addition to the already familiar smells of sweat, blood, and piss, the warm smell of cow shit permeated the crowded cramped space. The floor still had remnants of rotting straw and cow feed. The walls were lined with three-tiered nary made of rough-hewn pine boards. Judging by the smell, the boards came from old cow stalls. The nary were narrow, only two boards in width. And there weren’t enough of them. Abram tried to count the people in the train car but kept losing his count somewhere around 70. The nary could only hold 30.

Abram kept waking up every time his cheek touched the freezing metal of the train car’s wall. He thought about a newspaper article that he read once before the war, an article about a famous Polish psychic by the name of Wolf Messing. One part of that story that fascinated everyone was about Messing’s meeting with Stalin. According to the story, Stalin wanted to test Messing’s abilities. On Stalin’s orders, Messing walked into a Soviet bank, handed one of the cashiers a note and requested to withdraw 10,000 rubles. The note was actually a blank piece of paper. The cashier handed over the money and Messing walked out of the bank.

The part of the story that interested Abram the most was the one about Messing’s childhood. When Messing was a child, he got lost in the woods in the middle of the winter. As he began to freeze, Messing imagined that he was on a tropical beach, sweating from the heat. He managed to convince his body to ignore the deadly cold by the sheer power of his imagination.

Abram’s imagination wasn’t nearly as good as Messing’s. No matter how hard he tried to convince himself that he was sitting on a beach in Argentina instead of a freezing cattle car, his body continued to shiver. More than once he thought that maybe, just maybe, it would be better to freeze to death now than to dread the inevitable execution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.